The Charitable Community

By Marvin Olasky, published by World News Group on April 24th, 2018

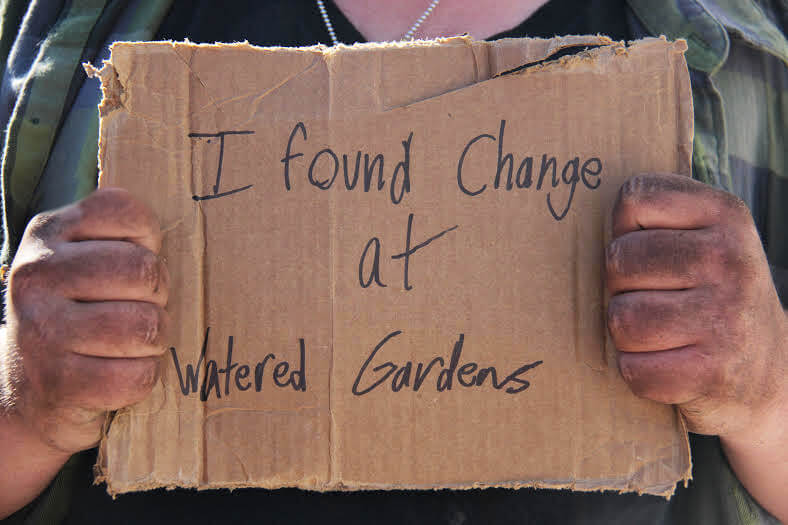

James Whitford received a doctorate from the University of Kansas School of Medicine, then moved on from rehabbing bodies to rehabbing lives. Whitford and his wife, Marsha, have given birth not only to five children but to the Watered Gardens Gospel Rescue Mission in Joplin, Mo., a city of 50,000. Here are edited excerpts of our interview in front of Patrick Henry College students.

Why the name, Watered Gardens? In Chapter 58 of Isaiah, God chastises His people for—in the short version—just going to church and not doing anything more. He goes on to say, “Is this not the path that I’ve chosen for you—to feed the hungry, shelter the poor, clothe the naked, welcome the poor into your house? Then you’ll be like a watered garden.” We see the blessing promised to God’s people when they’re helping struggling people be productive.

We’re happier when we’re more productive? The Journal of Applied Psychology in 2015 published a study of more than 6,000 adults. They were unemployed for more than four years but sustained by the government in another country. No work, but they had everything they need materially. The researchers apply psychometric measures. On agreeableness, openness, and conscientiousness, the adults dropped significantly compared with a control group. One result of people not working is grumpiness.

So poverty is not just a material question. Outside our mission doors one evening, a man stopped me and said, “I’ve been to a lot of different missions, but I’ve never been to one where I had to work for my bed and meals. You guys take the shame out of the game.” The guy standing beside him said, “We get to keep our dignity.”

We’re poor in dignity and also in relationships? The welfare system is so robust right now that there’s no need to develop relationships, either on the giving or the receiving side. When an elderly person has a cupboard full of government-subsidized food, you’re less likely to volunteer to prepare him a meal. Here’s the latest: Our government-subsidized distribution of smartphones with free data. Now people who are unhappy sink into this form of entertainment that’s been handed to them and that they haven’t had to work for. When the tug for relationship comes, they’ve been so placated by things given them that they’re less interested in developing a real relationship with someone else.

‘Chronic poverty and homelessness are almost always rooted in broken relationships of some sort.’

Aside from the smartphones, what other kinds of changes have you seen in the culture of poverty over the last 15 years? Younger people at Watered Gardens. State-funded agencies telling more and more people to be homeless so they’ll qualify for HUD’s Rapid Re-Housing program. I had a meal with a young man who said, “I was living with my mom and grandmother. Things weren’t going so well.” An agency said that if he would come and live at the mission, he’d probably qualify for his own house. It’s a strange web of incentives, starting at the federal level.

What’s wrong with supplying that young man with a house? A person doesn’t become homeless when he runs out of money. He becomes homeless when he runs out of friends. Chronic poverty and homelessness are almost always rooted in broken relationships of some sort—a broken relationship between a man and his family, between a man and his community, or between a man and God.

We’re both fans of Alexis de Tocqueville. What did he write in the 1830s that’s still relevant today? Tocqueville wrote in Democracy in America that when the state supplants fraternal social connections in a community, we have fewer of those associations—and when individuals find themselves in need, they’ll turn back to the state again—a crowding-out effect.

You also like his Memoir on Pauperism. Tocqueville pointed out two reasons a person works: to survive and to better his condition of living. Work/betterment is a natural cause/effect relationship that every person should be free to experience. Imagine if a person doesn’t work for fear that life wouldn’t get better or for fear that his life condition might even worsen. That’s what’s happening today. Our welfare policy has created an environment in which regular employment doesn’t seem to add up for many—and in some cases, at face value, it appears to worsen a person’s situation. Those who perceive work as punishment develop learned helplessness.

Tell us about your conversation with one man, Randy. On our fourth visit together, he mentioned that he was applying for a part-time job but had limited himself to about 15 hours of work per week, because “if I work more than that, I’ll lose my benefits.” He believes things will get worse for him if he works more. How sad. For Randy and countless others I work with on a daily basis at the mission, work is not adding up.

I want people to know about some of the programs you have going in Joplin. Great Britain now has a Cabinet-level “minister of loneliness,” but I suspect your Neighbor Connect program will work better. Neighbor Connect connects one neighbor’s need to another neighbor’s skill. We database what people are able to do and categorize them by skill. When we’re vetting needs, we watch for opportunities to get people together. We have volunteers preparing a meal and taking it to people who are elderly and in need. We watch for opportunities like that.

What does your Charity Tracker do? It tracks all of this information that swirls around in a benevolent community, all of the aid that an individual or family receives. We’re careful to protect privacy, but it allows us as a community to operate in a collaborative fashion: When we put in goals for an individual, those goals are then read by other organizations. We are in an Uberized society, and we’re figuring out different ways to make information count.

What is your True Charity Initiative? We start by pervasively educating a community through public service announcements. It can’t just be nonprofits and churches: The entire community has to understand. The PSAs would couple compassion and common sense for radio listeners and TV viewers. I’d hope to see communities form up to rethink charity. That might set the stage for policy change that respects and protects “subsidiarity,” where neighbors help neighbors and local churches and community organizations help neighbors before state and federal governments get involved. We need that because we’re now in a nation that’s sinking, with $21 trillion in debt and the divide between haves and have-nots widening.

You’d like to see a “Charity Zone” pilot program. To create a “Charity Zone,” churches and charities would form an association with the goal of having private local charity replace welfare. Charity Zone associations would partner with their local social service offices to offer food, cash and utility assistance, instead of having the government do it. Financing would be via a 50 percent tax credit that donors could receive for contributions to members of the association.

Is that idea getting any traction with legislators? Federal-level legislators give me a blank stare. State legislators get it and they’d be more than happy to try a pilot program, but their hands are often tied because welfare components are federally funded, with strings attached.