Redefining Poverty

I remember meeting a man on the main road through Fond Parisien, a small community on the eastern side of Haiti. He was walking along the dusty roadside pulling a two-wheeled dolly behind him. I didn’t understand the word he hollered out, but I recognized what was in his hand as he waved it exuberantly above his head. It was a popsicle. A cooler was secured on his dolly and in it were plastic wrapped popsicles packed like sardines. The thought of one in the middle of a scorching day at the medical mission was enough for me to strike up conversation. I don’t recall the words we exchanged, but I do recall the man’s vibrancy. Even through a language barrier that required an interpreter, it was obvious he was full of life and hope. I’m certain that purchasing his popsicles that day didn’t help him come close to crossing the threshold of poverty as we define it in America. And yet, he never seemed impoverished at all.

In contrast, I know many people in our city who, through state welfare, have much more materially than my salesman friend in Haiti, yet seem much more impoverished. One man showed up at our rescue mission a few days ago who I know from some time back. He once asked me why he should have to work for his food after I offered him an opportunity to earn a meal voucher. Not long after that encounter he qualified for food stamps and then state funded housing and even a government subsidized cell phone. But he’s homeless again and needing shelter. Why? Because the tens of thousands of dollars he received in government subsidized goods and services were only a form of poverty alleviation rather than poverty resolution.

How do we resolve it?

Maybe we should start by redefining it. We have long defined poverty at some material threshold. Currently a family of four with an income under $23,283 per year is “impoverished.” Don’t believe it. The longer we define it materially, the longer we’ll throw material at it as a solution. What if we used productivity as the measuring stick? After all, productivity and poverty mix like oil and water. Arthur Brooks explores the science of charity in his book, Who REALLY Cares? In it, he cites research that reveals a person on welfare is statistically more likely to say he or she is “inconsolably sad” than a working poor man at the same level of material poverty. Not only that, but the working poor will on average give 500% more to charity than the comparable welfare recipient. My point is this: More often than not, productive people are happy givers. They are not poor.

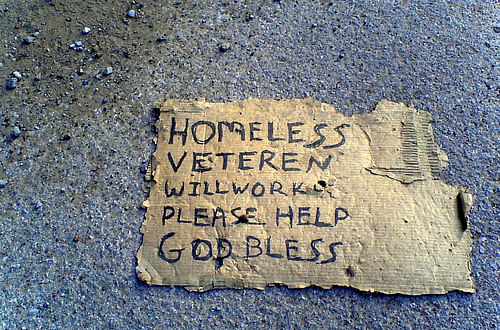

I see the incredible value of this in our mission every day. From the four fingered man who helped us stuff envelopes for a food basket to the homeless guy who helped mow lawns for his bed and meals, few things build self esteem and change the poverty mindset like productivity. So the next time you drive up to someone holding a sign that says, “Will work for food,” consider how you might take him up on the offer instead of handing him cash. For him, it could be the beginning of moving from poverty alleviation to poverty resolution.