Most of What You Believe About Poverty (Might) Be Wrong: A Summary of the Alternative

Amanda Fisher

Amanda Fisher

Community Engagement Director

Read more from Amanda

Network Director

Read more from Nathan

Listen to this article:

Jump to:

The Purpose of the Book | The Perspective | The Key Points | Details We Love | Considerations | Who Should Read This?

The Purpose of the Book

Author Mauricio Miller asserts that the programs and systems in place in the United States are based on failed assumptions and attitudes toward the poor. He offers an alternative approach to poverty alleviation that is focused on the strengths and self-determination of individuals.

The Perspective

Miller’s assertions regarding failed assumptions toward the poor stem from his experience in three relevant domains:

1) His family’s experience in poverty:

Fleeing to the United States in the 1950s with him (age 9) and his sister, Miller’s mother was determined to give them a better life. An intelligent and gifted seamstress, she came for opportunity, not charity or to live in “tolerable poverty.” Her plans derailed as she found it difficult to find and keep gainful employment because of others’ assumptions that their poverty was their fault, that they were “lazy, dumb, or dependent on the government.”

Miller’s family and others he knew were hard-working and resourceful rather than “victims waiting for saviors, but he witnessed the system’s “disdain for low-income families, primarily the parents…” even though his mother made a lifetime of sacrifices to create a better life for him.

Miller witnessed perverse incentives through the lens of his sister. Instead of benefitting from her initiative to leave an abusive husband and working to support her children, “…the safety net failed her,” becoming a barrier when she began to strive. Miller learned through this that the “less you have, the more you qualify.” He was motivated to find an alternative where those in similar circumstances could get a choice of benefits for the initiative taken toward independence.

2) His education:

Miller’s mother worked multiple jobs to save for Mauricio’s college at U.C. Berkeley, where his views on and response to poverty continued to form. His college attendance was at the height of 1960s activism and the beginning of the War on Poverty. Particularly inspired by the Black Pride movement and their ability to organize and encourage each other, their desire to control their own future left an indelible impression on him.

3) His nonprofit work and leadership:

During graduate school, Miller joined the nonprofit AND (Asian Neighborhood Design), where he would later serve as Executive Director for 20 years. Using their architectural and design expertise, AND renovated buildings for nonprofits joining LBJ’s War on Poverty. They recruited kids in gangs to work, teaching them construction skills as a way out of gang life. It was during this time that he “saw fundamental flaws in how the war on poverty was being waged.” The program required that they accept the neediest individuals, which incentivized kids to commit crimes and live on the streets to get chosen. Miller saw that help seemed reserved for those who were getting into trouble rather than those who were trying to stay out of trouble. Clients had to show their worst side rather than their talents.

Miller found that more financial support was available for AND if he implied to government funders that parents were “disengaged, uncaring, or incapable” and that the participants were more at-risk and needy. The organization was incentivized to view people based on deficits and communicate that to funders. He became frustrated with the system, resenting having to please funders instead of doing what was right for clients.

Miller’s experiences ignited his enthusiasm for an alternative solution. The systems in place were not good for him and his family as immigrants, for the activists he encountered who sought control over their lives, or for the kids attempting to get out of gangs in his nonprofit work.

The Key Points

Replacing A Deficit View

Miller addresses “Our Fundamentally Flawed System,” stating the prevailing “deficit view” of low-income families neither allows for initiative and talent to be discovered nor invested in. This focus on needs rather than contributions creates a “race to the bottom” instead of the top. Further, Miller addresses the damage caused by the “Us and Them” mentality between professionals and those in poverty. Woven through his experiences is his recognition for an alternative solution that must:

- Recognize peoples’ resourcefulness and strengths: discover, then match people’s efforts

- Let people learn their own lessons: don’t intervene to save them from every “bad idea”

- Give the benefit of the doubt: assume parents are engaged and capable; trust them until they prove otherwise

- Incentivize growth: give more to those who are growing, not those who are becoming worse off

- Build community: help people rely on their peers and bolster existing personal relationships

- Use technology for people to record progress toward goals and share ideas

Three Alternative Components

In the second section, Miller recommends “Putting Families in the Driver’s Seat.” In 2001, Miller began doing this through the Family Independence Initiative (rebranded later to UpTogether), focusing on:

- Control – well-intentioned workers must relinquish control to families to lead their own change. Although they can assist with engagement, a hands-off approach is a must.

- Choices – Often, people in poverty have limited choices. The alternative solution offers matching funds to committed families in order to increase their options.

- Community – Success stems from people working together rather than individually, so the alternative honors and supports group effort.

Implementation Ideas

Miller details specifics of his “Alternative”:

Self-recruiting – Those interested in improving their lives recruit others who are interested in doing the same. Groups hold each other accountable through regular meetings. An UpTogether liaison meets with them monthly to hear their stories, goals, and challenges.

Data collection and verification – When families enroll, UpTogether collects baseline data on categories such as income, expenses, food stamps, bank accounts, debt, credit score, child support, education, skills, health, housing, and civic activities. UpTogether staff verifies data quarterly through documents like pay stubs, bank accounts, and report cards.

Journaling system – Families enter data in a cloud-based system each month, a much cheaper and more sustainable option than having a paid employee enter the information. Tracking their own progress provides instant feedback; they see the results in real-time (i.e., a graph showing the income line going up or down). They can also see the progress of their cohort, as well as the general progress of other groups, offering an element of competitiveness.

Online Community – Similar to other social networking platforms, UpTogether.org provides an online community of support for participating families as they connect, form groups, discuss topics, and make recommendations.

Resource Hub – In exchange for the information and the time it takes families to provide it, UpTogether pays families (approximately $100/month) or gives scholarships. Additionally, UpTogether offers a Resource Hub where families are given a choice of additional awards. Some examples are matching funds for dollars saved, assistance with college tuition, or low-interest loans. They also offer a Family Time Fund for families to save and receive matching dollars for spending quality time together. This not only strengthens family relationships but is also more cost-effective than paid staff taking youth on a trip or to an event.

Details We Love

We agree with Miller that the “deficit view” of people is undignifying. Because every person has unique giftings as God’s creation, we should get to know them and find their strengths rather than focusing on their dysfunctions or comparing their situation to another’s. Miller’s family experienced difficulties caused by assumptions made regarding his family’s poverty; we agree that poverty fighters should be observant but without assumption.

Miller’s alternative focuses on strengthening relationships of family and close friends. He states, “Our society takes family and community for granted but it shouldn’t…personal loving relationships are far more transformative than social programs – and they cost a lot less, too.” We agree that these relationships should be the primary source of help rather than interventions by institutions or outsiders. According to Miller, “Working with and empowering families, parents, extended family or guardians is the future of social work.”

Miller has a profound understanding of the importance of social capital since he has experienced varying levels of socioeconomic status. As he rose above poverty through education and work, he began to benefit from his new-found connections, from gaining employment, to good restaurants, to getting a dog.

Miller’s Alternative emphasizes collecting data to drive motivation and measure success. We also recommend that poverty-fighting organizations measure outcomes to ensure they are reaching their goals.

True Charity Network members have access to the Outcomes Toolkit, a booklet containing detailed guidance on how to transition to measuring long-term impacts, such as stable housing, employment, education, and family reunifications. Non-members, learn more about our Toolkits!

Considerations

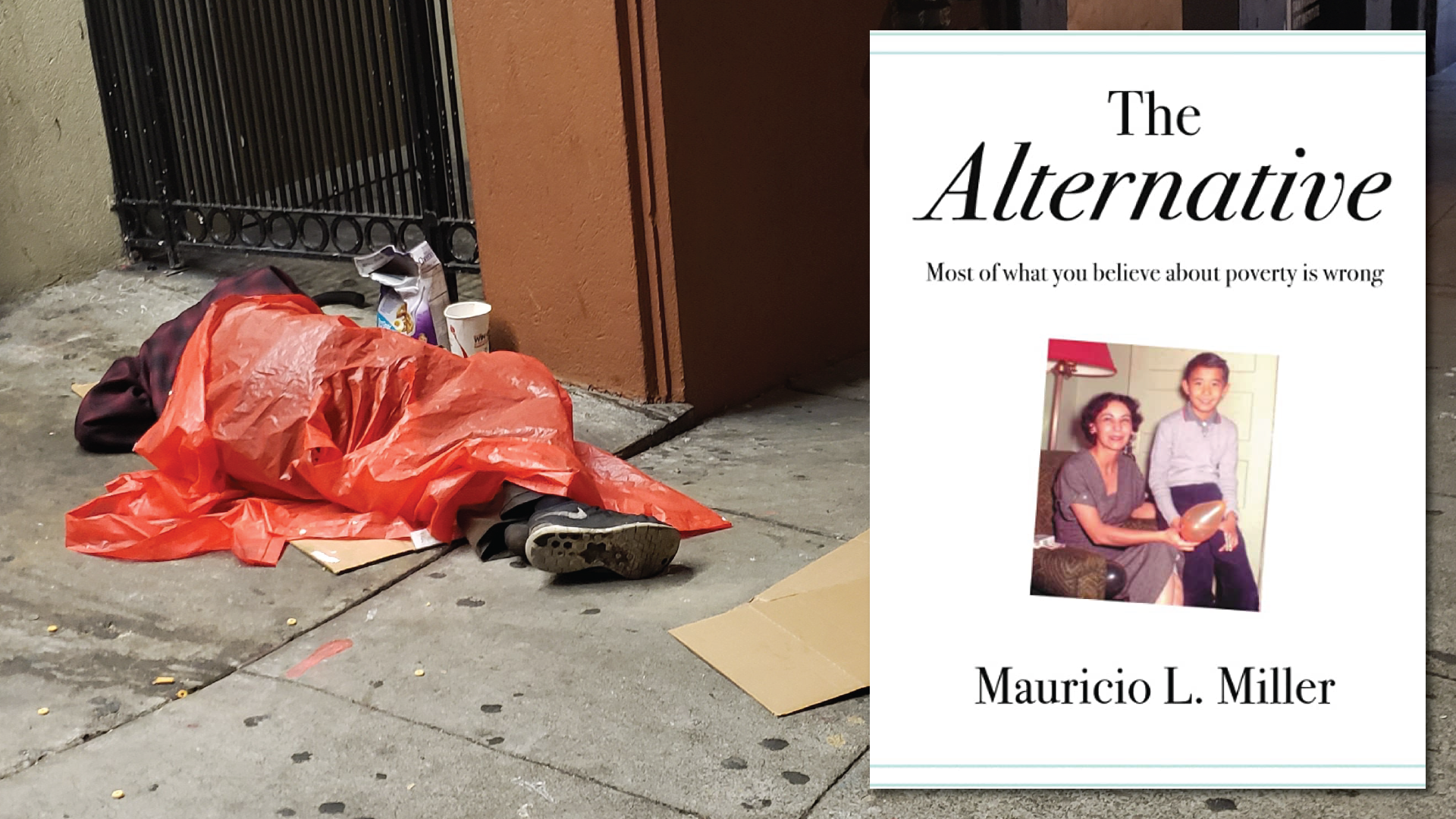

While Miller offers valid and devastating critiques of the current approaches to poverty alleviation, his own solutions seem more limited in application than he admits. The prevailing theme throughout the book is that poor families always have solutions to their own problems and need no outside guidance, just a little connectivity and social capital. This doesn’t address demographics that are under-equipped to solve their own problems without any guidance, such as the severely addicted, the chronically homeless, young adults aging out of foster care, and the intergenerational poor. While these people also have assets and capabilities, it stands to reason that they need more guidance or conditional assistance than some of the families Miller works with.

Miller’s solutions are strongly informed by his personal experience as a second-generation immigrant. But his own experience proves that his family was more the exception than the norm. Even though Miller felt his family was utterly failed by the poverty alleviation field, he ended up attending an elite university within a decade of arriving in the country. If all poor families were like Miller’s, intergenerational poverty would be practically nonexistent. As evidenced by the fact that they left their home country to make a better life for themselves, immigrants tend to have an exceptional drive towards rising out of poverty and nearly always succeed for their children if not for themselves.

Miller’s experiences with the highly motivated poor continued with the community he organized through UpTogether (founded in immigrant-dominated California). Since UpTogether relies on referral recruiting by motivated participants, it tends to build a community of people very similar to Miller’s family. This is no doubt excellent for the participants, and we have no issues with building self-selected communities committed to growth. However, this does mean that just because Miller’s system of no-strings cash and community may be exactly what his mother needed, that does not prove it will work as a first step for people who have been dependent on welfare for generations.

Miller expresses indignation at characterizations of some of the poor as lacking work ethic (such as former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich’s claim that “Really poor children in really poor neighborhoods have no habits of working and have nobody around them who works”). This overlooks that there are different types of people in poverty. Some of whom are the virtuous strivers that UpTogether assembles, and others of whom may lack character or skills. We suspect that significantly increasing no-strings-attached cash payouts in government programs (as the UpTogether website supports) would be especially harmful to the latter.

One other consideration is that, like many in the poverty alleviation field, Miller has strong opinions about word meanings. He objects to calling “the alternative” a program, even though a program is generally defined as a set of related activities with a particular long-term aim. While we understand that he is emphasizing the client-led nature of “the alternative,” refusing to categorize it by standard rules of language makes it more confusing rather than more clear.

Similarly, he also insinuates that all “charity” is bad: “Charity doesn’t instill pride, and programs led by professionals don’t instill pride or self-confidence.” While we fully agree that much done in the name of charity is counterproductive, by definition, charity is “generosity and helpfulness, especially towards the needy and suffering.” Just because our attempts at helpfulness are often unhelpful doesn’t mean we need to jettison the word any more than medical malpractice means we need to abandon the word “medicine.”

Who Should Read This?

Nonprofit leaders interested in bolstering relationships and focusing on the strengths of individuals will find Miller’s shared experiences, stories, and research motivating. Although there is not a specific spiritual component to The Alternative, church leaders and volunteers may benefit from Miller’s perspective as they help people identify and develop their unique God-given strengths and build social capital.

Miller provides principles behind The Alternative as well as details of how it works. However, it is meant to be shaped by the participants, so the specifics may look different from cohort to cohort or city to city. The information provided is more philosophical and less a step-by-step program, which is helpful for those who want to better understand the barriers immigrants and minorities encounter as they seek a flourishing life. For those who are seeking a program that provides specific courses and detailed guidelines, this book is not for you.

Already a member? Access your resources in the member portal.