A Framework for Flourishing: A Synopsis of When Helping Hurts

Nathan Mayo

Nathan Mayo

Vice President of Operations & Programs

Read more from Nathan

Updated from the Original Synopis Published Aug 5, 2021

Jump to:

The Purpose of the Book | The Perspective | The Key Points | Details We Love | Considerations | Who Should Read This? | The Sequel

When Helping Hurts is a rallying cry for the Church that simultaneously convicts and compels. Steve Corbett and Brian Fikkert set out to awaken American Christians to the stark contrast between their beach vacations and the grinding poverty in foreign slums. However, they don’t intend to stop at motivating just any action. They also provide a framework for understanding when “helping” is counterproductive and how to make a real difference by “walking with the poor in humble relationships.”

This book is written from a distinctly Christian perspective and is directed at the local church, with concepts easily applied by nonprofits, as well. This book also takes a global perspective on poverty but does not neglect the manifestations of poverty at home. The authors assert that it is unacceptable to do nothing and equally unacceptable to just do anything. “We do not necessarily need to feel guilty about our wealth. But we do need to get up every morning with a deep sense that something is terribly wrong with the world and strive and yearn to do something about it.”

Part 1: Foundational Concepts About Poverty. This book takes the theological perspective, along with the apostle James (1:27), that religion is not merely an exercise in personal piety but an exercise in living out piety in service to others. The authors express that many Christians make the mistake of exalting the King while caring nothing for his kingdom.

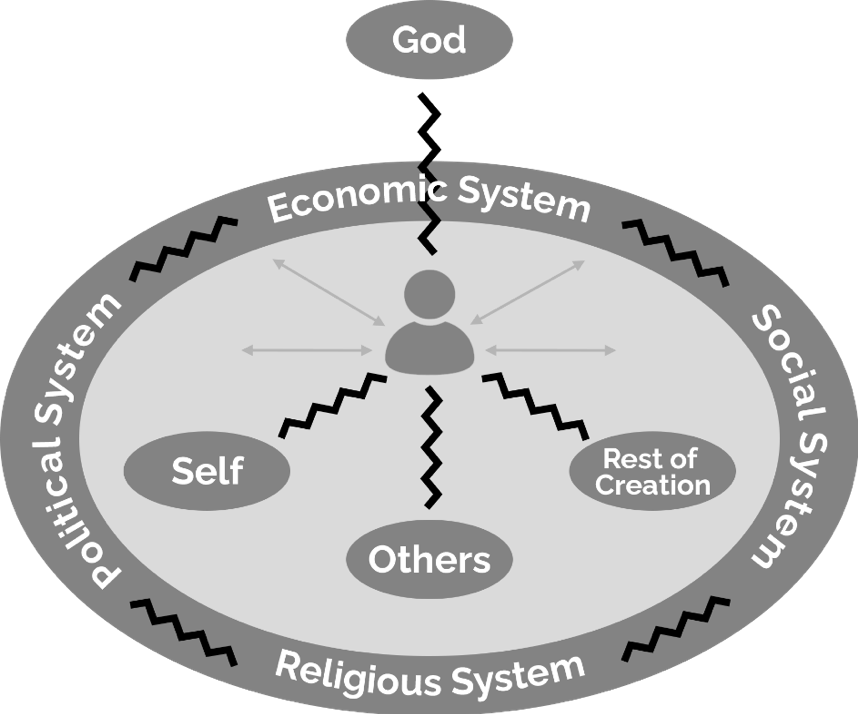

Furthermore, root cause analysis is critical to addressing poverty. The well-off tend to define poverty in physical terms—the poor tend to describe it in psychological terms such as humiliation, shame, powerlessness, and isolation. While root causes vary situationally, all can be categorized in terms of a breakdown of four key relationships: the relationships of individuals with themselves, with others, with God, and with creation.

Adapted from the graphic used in When Helping Hurts, by Brian Fikkert and Steven Corbett.

Dysfunctions in these relationships affect all of us regardless of how much money we have in the bank. Because of this, we must come alongside the poor with humility, not as superior saviors. However, though we all experience some brokenness, the authors are quick to point out that the physically poor are in an especially dire situation, held captive by a “spider’s web” of interconnected problems which makes it very difficult for them to escape unaided.

They clarify that the goal of poverty alleviation is not to merely transform the poor into the middle class (“a group characterized by high rates of divorce, sexual addiction, substance abuse, and mental illness”). Rather the goal is to “reconcile the four foundational relationships so people can fulfill their callings of glorifying God by working and supporting themselves and their families with the fruit of that work.”

The authors also add that both individual characteristics, such as worldview, and broken systems contribute to dysfunctions in these relationships. Addressing poverty means addressing internal and external circumstances.

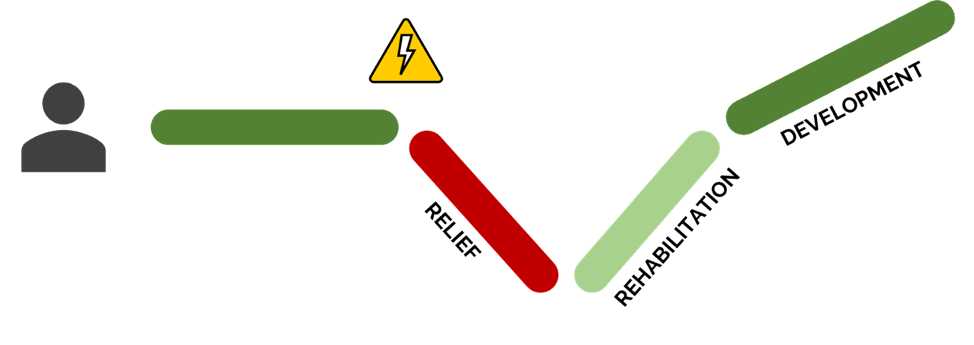

Part 2: General Principles. One of the most important contributions of this book to the effective poverty lexicon is the three types of charitable interventions. While poverty is complex, its solutions can be grouped into three broad categories: relief, rehabilitation, and development. A temporary crisis, such as a natural disaster or unemployment, requires relief, characterized by one-way giving designed to alleviate immediate suffering. Returning to the pre-crisis state, such as rebuilding a home or finding a new job requires rehabilitation, characterized by the recipient becoming an active participant in his or her own recovery. Advancing to a higher level of flourishing than previously experienced, such as getting a better home or job, requires development. Development and rehabilitation require the same basic intervention—both require active participation from the individual advancing.

Adapted from the graphic used in When Helping Hurts, by Brian Fikkert and Steven Corbett.

Effective relief is seldom, immediate, and temporary. Effective development recognizes the importance of doing with not for. A general admonition is to never do things for people that they can do for themselves.

The book also instructs leaders to invert the way they approach the poor. Do not see them as only having needs. Begin with their assets; assume they can do something and ask them about their capabilities before you design any programs to address their needs. The authors preview several tools to assist with this asset-based community development (ABCD). These include asset mapping, techniques for identifying the assets of a community; participatory learning and action, optimized for groups used to making community decisions; and appreciative inquiry, an approach that emphasizes what is working already and seeks to amplify it.

The authors also remind us that participation from the poor is an end unto itself, even if it does not seem to change the program much. Participation means people are overcoming their sense of powerlessness.

Part 3: Practical Strategies. The third section of the book provides some practical models of ministry at home and abroad.

In the US, they observe that poverty has “suburbanized.” The majority of the poor no longer live in inner cities but in rural and suburban areas in easy reach of churches. They acknowledge a wide range of obstacles the poor face, including difficulty accessing work, sufficient financial tools, and avenues for wealth accumulation. They also address the barriers created by low-quality schools and expensive healthcare and housing but recognize that it is difficult for a single church or nonprofit to impact these areas with limited resources. They propose strategies to address the most accessible elements of the problem, such as job training, financial education, food co-ops, and affordable Christmas markets. They also encourage churches to provide temporary employment to people and use their congregations to connect the poor to better long-term employment.

In a developing world context, they assess the value and limitations of the short-term mission team, which they compare to an elephant dancing with a mouse. Despite their potential to trample local efforts, mission teams can also do a lot of good, and the book provides some approaches for this purpose. Beyond the short-term interventions, they also unveil some the pros and cons of strategies like microfinance, savings and credit associations, business training, and social enterprises in developing countries. All of their strategies focus on empowering people to help themselves and are pragmatic about the limits of what a foreign partner can do.

Part 4: How to get started. A local church can work either at the level of an individual household or at the community level, generally through an organization or church based in the community. There are pros to both approaches. It is easier to start small by working with individuals. However, in many cases, helping an individual make major improvements to her life will result in her leaving a poor community and may have a net negative effect on those who remain. Hence the value of more collective efforts.

In either case, Corbett and Fikkert lay out five key principles for fostering change

1) Foster triggers for change. Change is usually inspired by a “trigger,” such as a recent crisis, the status quo becoming unbearable, or the introduction of a new idea. Organizations can look for clients who have experienced a crisis, refuse to alleviate the continued consequences of bad decisions, and use new possibilities to impact the triggers that will inspire change.

2) Mobilize a supportive community. Volunteers have an important role to play in supporting, mentoring, and connecting people in poverty to better opportunities. Mobilize them, and place them in structures that facilitate relationships, not dominance.

3) Look for an early, recognizable success. “Start small, start soon, and succeed.” The best way to get started is with a small goal or objective that a poor person can choose, contribute to meaningfully, and see accomplished. This helps build confidence for more ambitious projects.

4) Learn the context as you go. It is important to understand the details of a person’s situation, but some can be learned in progress to facilitate more rapid action. There should be a natural loop of trying something together then reflecting together and trying something new.

5) Start with the people most receptive to change. Since development cannot be done to someone, it naturally requires a willingness to change. The authors list a seven-step continuum describing levels of receptivity to change. Because your resources are limited, in any program, it makes sense to triage assistance by willingness to change.

This book is paradigm-forming and has sounded a clarion call for Christians concerned about the poor. They build the case for why all Christians should care, and why caring, coupled with sound understanding, should lead to more effective practice.

While it is impossible to unpack the implications of these ideas fully in a single book, the authors do their best to lay out practical strategies.

The ideas of this book inform the entire True Charity philosophy. Central to the book is the idea that development requires what we call “challenge.” Although they do not spend any time talking about outcome measurement, they clearly support a results-focused orientation—with the appropriate caveat that people are not widgets, and building the relationships that lead to good outcomes is an intensive process. We also appreciate that they acknowledge the centrality of relationships and faith in effective charity, recording an instance when they turned down a government grant because it would have required them to extract the Christian elements from their job-training program. It follows that while the government has some role in poverty alleviation, it cannot be a primary one.

In their efforts to clarify the root of poverty, the authors express all the malfunctions of the four relationships in terms of poverty: “poverty of being,” “poverty of community,” “poverty of stewardship,” and “poverty of spiritual intimacy.” This introduction of new terms then forces them to explain why “material poverty” is a matter of greater cause for mobilization than a wealthy person suffering from “poverty of community.” While we agree with their central point that imperfection is universal and humility is critical, the reframing of all maladies of existence as “poverties” and proclaiming that we are all poor tends to confuse people as to why they should care especially about the “material poor.”

The authors point out examples of broken systems to explain the interaction between personal choices and factors beyond a person’s control. While the general point is well taken and the authors attempt to be fair, several of their specific examples of the effects of racism, predation, and other injustices are more debatable than they acknowledge. In other words, systems asserted as examples of root causes, are often the aggregate effect of personal choices or political incentives other than those the authors identify. In any event, the book is not intended as political or economic commentary and should not be read as such.

This is a foundational read for any Christian nonprofit leader or church leader. If you have not read this yet, it should be next on your list. Any Christian could benefit from the perspective provided by this book.

Brian Fikkert, along with theologian Kelly Kapic, go deeper into the theological foundations of When Helping Hurts in their sequel, Becoming Whole. Learn more about that book here: Salvation, the American Dream, and Becoming Whole: A Sequel to When Helping Hurts – True Charity

2025 Update: Dr. Brian Fikkert, co-author of When Helping Hurts, has now been announced as a keynote speaker at the 2025 True Charity Summit on April 9–11 in Huntsville, Alabama.

This article is just the tip of the iceberg for the practical resources available through the True Charity Network. Check out all of the ways the network can help you learn, connect, and influence here.

Already a member? Access your resources in the member portal.