Jump to:

How Are We Doing? | Dependency & Paternalism | Look Up | Expect Up | Size Up

Some days more than others, I wait with just a bit more earnest desire for the new heaven and new earth Peter wrote about at the end of his second letter (2 Peter 3:13). Nationally, we’ve seen homelessness rise for the last handful of years, and for the last few decades, the poor have been slipping into deeper poverty. On the world stage, we’re witnessing events that none of us have seen before unless we were around for the Second World War and the Spanish flu. Whew. Things are far from the perfected end we read about in Scripture — that day when all things will be made right, or fully justified, as they ought to be.

But, as compassionate ministry leaders, you and I live and work in a world much more granular than homeless counts, poverty levels, quarantine numbers, or inflation rates. We’re dealing with unique individuals, some who have dashed dreams, others wounded hearts, and many with broken minds or bodies or both. It rarely takes more than a five-minute conversation with a person in one of our missions to recognize injustice: not the injustice levied by some past abuser or a corrupt institution, but the unjust condition that’s simply opposite of the final and just condition described in the Bible.

In his book, Pursuing Justice: The Call to Live and Die for Bigger Things, Ken Wytsma describes truth as pertaining to what is and justice as what ought to be. This idea of justice elevates us above discussions of social justice or distributive justice and points us toward biblical restorative justice. As we pray for God’s will to be done on earth as it is in heaven, we are praying for this kind of justice — that life around us in our families, ministries, and communities would be more as it ought to be. For many of us, our passionate pursuit of this is the dedicated work of our lives. It is for justice that we fight, with great faith and hope of helping one person at a time step into a better life — one that is more as it ought to be.

How Are We Doing?

Well, it’s a hard calling with a tough job to match, isn’t it? Yet we’re a driven and motivated bunch, and certainly those qualities, with earnest prayer, have resulted in some great testimonies from our missions and ministries. It’s time to level up, though. I know, I know. Level up? Are you kidding me? I can barely keep pace at the level I’m on! I get it. There’s no more drive or motivation to muster up. I’m with you, and I’m not suggesting you muster it up. I’m suggesting you transfer it. Right, transfer your motivation and drive to those you’re helping. Successfully transferring that motivation to the person you’re motivated to help is one way to bring just equity into what is often an unhealthy and imbalanced relationship, one in which the recipient is dependent and the giver, paternalistic (not to mention overworked!).

Well, it’s a hard calling with a tough job to match, isn’t it? Yet we’re a driven and motivated bunch, and certainly those qualities, with earnest prayer, have resulted in some great testimonies from our missions and ministries. It’s time to level up, though. I know, I know. Level up? Are you kidding me? I can barely keep pace at the level I’m on! I get it. There’s no more drive or motivation to muster up. I’m with you, and I’m not suggesting you muster it up. I’m suggesting you transfer it. Right, transfer your motivation and drive to those you’re helping. Successfully transferring that motivation to the person you’re motivated to help is one way to bring just equity into what is often an unhealthy and imbalanced relationship, one in which the recipient is dependent and the giver, paternalistic (not to mention overworked!).

You might recall Robert Lupton’s five steps to dependency from his book, Toxic Charity: How Churches and Charities Hurt Those They Help (And How to Reverse It): If you give something to someone once, the person will appreciate it. If you give it a second time, he’ll develop an anticipation that you might do it a third. If you do it a third time, he’ll expect you’ll do it a fourth. A fourth time, he’ll feel entitled to the transfer, and a fifth time, he’ll be dependent on you for it.

Appreciation, Anticipation, Expectation, Entitlement, Dependency. Because we live in community with the people we help, this type of unhealthy reliance is not without its countereffect on the well-intentioned charitable soldier. Consider these five steps to paternalism that occur in concert with the downward march toward dependency: Giving something to someone results first in a sense of exhilaration. Again, and you may feel a deepening purpose in relation to whom you’re helping. A third time and you’ll feel necessary. A fourth, essential and a fifth, paternalistic. Exhilaration, Purpose, Necessary, Essential, Paternal.

How Are We Doing?

Well, it’s a hard calling with a tough job to match, isn’t it? Yet we’re a driven and motivated bunch, and certainly those qualities, with earnest prayer, have resulted in some great testimonies from our missions and ministries. It’s time to level up, though. I know, I know. Level up? Are you kidding me? I can barely keep pace at the level I’m on! I get it. There’s no more drive or motivation to muster up. I’m with you, and I’m not suggesting you muster it up. I’m suggesting you transfer it. Right, transfer your motivation and drive to those you’re helping. Successfully transferring that motivation to the person you’re motivated to help is one way to bring just equity into what is often an unhealthy and imbalanced relationship, one in which the recipient is dependent and the giver, paternalistic (not to mention overworked!).

Well, it’s a hard calling with a tough job to match, isn’t it? Yet we’re a driven and motivated bunch, and certainly those qualities, with earnest prayer, have resulted in some great testimonies from our missions and ministries. It’s time to level up, though. I know, I know. Level up? Are you kidding me? I can barely keep pace at the level I’m on! I get it. There’s no more drive or motivation to muster up. I’m with you, and I’m not suggesting you muster it up. I’m suggesting you transfer it. Right, transfer your motivation and drive to those you’re helping. Successfully transferring that motivation to the person you’re motivated to help is one way to bring just equity into what is often an unhealthy and imbalanced relationship, one in which the recipient is dependent and the giver, paternalistic (not to mention overworked!).

You might recall Robert Lupton’s five steps to dependency from his book, Toxic Charity: How Churches and Charities Hurt Those They Help (And How to Reverse It). If you give something to someone once, the person will appreciate it. If you give it a second time, he’ll develop an anticipation that you might do it a third. If you do it a third time, he’ll expect you’ll do it a fourth. A fourth time, he’ll feel entitled to the transfer, and a fifth time, he’ll be dependent on you for it.

Appreciation, Anticipation, Expectation, Entitlement, Dependency. Because we live in community with the people we help, this type of unhealthy reliance is not without its countereffect on the well-intentioned charitable soldier. Consider these five steps to paternalism that occur in concert with the downward march toward dependency: Giving something to someone results first in a sense of exhilaration. Again, and you may feel a deepening purpose in relation to whom you’re helping. A third time and you’ll feel necessary. A fourth, essential and a fifth, paternalistic. Exhilaration, Purpose, Necessary, Essential, Paternal.

How Are We Doing?

Well, it’s a hard calling with a tough job to match, isn’t it? Yet we’re a driven and motivated bunch, and certainly those qualities, with earnest prayer, have resulted in some great testimonies from our missions and ministries. It’s time to level up, though. I know, I know. Level up? Are you kidding me? I can barely keep pace at the level I’m on! I get it. There’s no more drive or motivation to muster up. I’m with you, and I’m not suggesting you muster it up. I’m suggesting you transfer it. Right, transfer your motivation and drive to those you’re helping. Successfully transferring that motivation to the person you’re motivated to help is one way to bring just equity into what is often an unhealthy and imbalanced relationship, one in which the recipient is dependent and the giver, paternalistic (not to mention overworked!).

Well, it’s a hard calling with a tough job to match, isn’t it? Yet we’re a driven and motivated bunch, and certainly those qualities, with earnest prayer, have resulted in some great testimonies from our missions and ministries. It’s time to level up, though. I know, I know. Level up? Are you kidding me? I can barely keep pace at the level I’m on! I get it. There’s no more drive or motivation to muster up. I’m with you, and I’m not suggesting you muster it up. I’m suggesting you transfer it. Right, transfer your motivation and drive to those you’re helping. Successfully transferring that motivation to the person you’re motivated to help is one way to bring just equity into what is often an unhealthy and imbalanced relationship, one in which the recipient is dependent and the giver, paternalistic (not to mention overworked!).

You might recall Robert Lupton’s five steps to dependency from his book, Toxic Charity: How Churches and Charities Hurt Those They Help (And How to Reverse It): If you give something to someone once, the person will appreciate it. If you give it a second time, he’ll develop an anticipation that you might do it a third. If you do it a third time, he’ll expect you’ll do it a fourth. A fourth time, he’ll feel entitled to the transfer, and a fifth time, he’ll be dependent on you for it.

Appreciation, Anticipation, Expectation, Entitlement, Dependency. Because we live in community with the people we help, this type of unhealthy reliance is not without its countereffect on the well-intentioned charitable soldier. Consider these five steps to paternalism that occur in concert with the downward march toward dependency: Giving something to someone results first in a sense of exhilaration. Again, and you may feel a deepening purpose in relation to whom you’re helping. A third time and you’ll feel necessary. A fourth, essential and a fifth, paternalistic. Exhilaration, Purpose, Necessary, Essential, Paternal.

Dependency and Paternalism

Though intentions may be honorable, both local and national efforts to address poverty through simple, transactional charity not only have failed to close the income gap but have widened the relational one. A strange codependency between the recipient and the provider continues to feed the hungry without ever solving hunger, shelter the poor without solving homelessness, and transfer wealth without ever empowering people to create it themselves.

Across our land, people are reading the papers or watching the news, shaking their heads, wondering how the problems of poverty and homelessness can be solved. Let’s provide the answer. We are the leaders to set a new standard, modifying or creating innovative programs that flip the steps. Yes, flip the steps to dependency and paternalism, leading a renewed national vision of communities marked by an exhilarated and appreciative people, not codependent but interdependent. In fact, our goal should be to bring these two groups so close together that we can’t tell the difference between them. Can the provider be a recipient and the recipient a provider?

These ideas sound a little lofty, I’ll agree. Here are some practical questions to ground us a bit: How do we shift the balance of our programs from relief towards development? How can we meet vital and basic needs repetitively without also being complicit in the dependency trap? How can we motivate the people we help to do more to help themselves?

How can we level up?

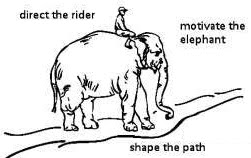

Look up, expect up, and size up.

– 1 –

Look Up

Being a member of Citygate Network, it’s unlikely you have a cultural problem in which staff or volunteers at your mission look down on people. But do they “look up” to people? Looking up to a person is to admire a personal quality, respect an achievement, or recognize a gift in a person. That’s tough when you’re sitting across from someone who has been ravaged by the elements, is dazed by the latest drug, or is wildly confused and incoherent. Where is that quality, achievement, or gift to admire, respect, and recognize? This is where compassion fails us. Don’t get me wrong — compassion is vital and we’re certain to fail without it. It’s awakened by the injustice and brokenness we see in lives around us and it is what fuels us to act, but it is Christ’s vision that enables us to see beyond the physical to recognize the inherent dignity and worth in even the most wretched and wrecked soul. Through the eyes of Christ, we are able to see beyond the physical to the imago Dei — the image of God. And when we do see it — that nobility of God residing in a person — our faith is suddenly ignited to believe that what ought to be is attainable.

When Jesus landed on the shore of the Gerasenes, he was met by a naked, self-destructive man who lived among the tombs. You know the story. Jesus saw what ought to be. He delivered the man from his demons and left him clothed and in his right mind (Luke 8:35). When Jesus stepped out of the boat and first saw this tormented and possessed man approach Him, don’t you think He also saw a man clothed and in his right mind? We need Christ’s vision if we’re going to “look up” to people we serve.

One way to develop the look-up culture in your ministry is to adopt the right terminology. Are the people you serve “residents” or “guests”? Are those in your social enterprise “clients” or “partners”? The culture of looking up is also reinforced by a ministry’s core values, ensuring that respect of inherent human dignity is included. Noble creation, imagebearer, human dignity, highly esteemed, ennobled may be words to consider in the adoption or revision of a core value. As an example, one of the core values at our mission is Human Dignity — Every Person is a Noble Creation. Regardless of how you choose to emphasize it in your ministry, remember this truth: What you value is what you cultivate, and what you cultivate becomes your culture. So value “looking up.”

– 2 –

Expect Up

How you and I view people informs how we treat them, and how we treat them influences how they respond. If we look up to a person and genuinely respect his or her God-given gifts and abilities, then shouldn’t we “expect up,” also? Having no expectations communicates, “You’re unable.” Lowered expectations speak, “I don’t think you can do it.” But right expectations of a person communicate, “I believe in you.” Those are four words too many have never heard before. And remember, how we treat people impacts how they respond. If we don’t “expect up,” who will rise up?

“Expecting up” is a major encouragement and motivation to people, and we see it throughout Scripture. The word if is found over 1,400 times in the Bible, often linking God’s expectation to some reward or blessing. Second Chronicles 7:14 is one of those that many of us know by heart: “If my people, who are called by my name, will humble themselves and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven, and I will forgive their sin and will heal their land.” God’s expectation for us is clear, and many of us are motivated by it! We also see expectation in the New Testament. In John 8, Jesus verbalized His expectation of the woman He had forgiven of adultery: “Go now and leave your life of sin.” I’m sure the blend of His grace and expectation motivated her to change.

In our ministries, motivation by expectation starts with a search for the ability and gifting of a person. Expect to find it. This is the practice of function-based categorization. Rather than simply qualifying a person as a recipient of a particular program because of his or her poverty level or disability (dysfunction-based categorization), consider placing equal energy during your assessment on uncovering a person’s capacity, potential, and functional ability. You may have a tool that helps with this, or you might want to consider a SWOT box assessment tool. This tool helps any person consider not only Weaknesses and Threats but, more importantly, Strengths and Opportunities in the areas of education, work, relationships, and health. True Charity has a SWOT box assessment tool you can use; you can find it here: www.truecharity.us/swot

If you discover the person you’re assessing has ability (and most do), then expect exchange. That’s not to say that there aren’t situations in which one-way handouts are necessary, but they should be rare and few. Most people have the capacity to exchange a little of their time and talent for what they need. Expect it.

The father of modern economics, Adam Smith, noted something very simple but profound in his seminal work, The Wealth of Nations: “Nobody ever saw one animal by its gestures and natural cries signify to another, this is mine, that yours; I’m willing to give this for that.” Although we intuitively know this, its implications are weighty. Exchange is a unique aspect of humanity found in markets. So when we strip people of their opportunity to exchange something they can do for something they need, we also strip them of some aspect of their humanity. An expectation of exchange spares both parties from falling into the trap of dependency and paternalism.

Practically speaking, consider establishing an “earn it” program. Creating a way for people to exchange a little of their time to earn vouchers that can be traded for basic needs is a powerful way to “expect up” and break free from an unhealthy dependency model. It’s not an easy lift to shift your model of ministry to an “earn it” model, but its rewards are great. Having folks work in various spots of your ministry or help in one of your social enterprises for even short amounts of time to earn an item from your thrift store or food from your pantry is an empowering form of charity that reminds people they were created to be more than the recipients of someone’s benevolence. Your community will likely embrace your new approach as you communicate your inspiring belief in the people you serve and how you are providing them opportunities to experience the joy of purposefulness and contribution.

Depending on the size and history of your ministry, the work of transitioning to an “earn it” model can vary. It’s not the only way to level up your expectation, though. You might start with good goal writing. Taking case management beyond resource connection to dreaming, planning, and establishing goals is a great way to introduce expectation. I prefer the PIVOT acronym to guide the process. Goals should be action steps that Point to the vision, are clearly Identifiable, Verifiable, Owned by the individual, and Time-driven.

Lastly, sharing those goals and other case management information with like-minded organizations serving the same families and individuals is another way to address unhealthy dependency in your community. There are different tools to accomplish this, but one easy, web-based option is Charity Tracker. In one Oregon community, we use Charity Tracker to connect one ministry’s thrift store to a vocation-training ministry in the same town. Rather than continue with a handout model for folks who have no money, the thrift store allows people to shop and then tallies the time required to earn the items, enters that information in the Charity Tracker system, and then sends the individuals down to the training center. Once the time is completed, personnel at the training center enter it in the system and the people are free to pick up their items from the store.

We’ve connected scores of churches and nonprofits together with this tool which aids in ministering more seamlessly and cohesively, and stems the tendency for dependency to form in an otherwise benevolent but disconnected community. This type of practical collaboration collectively signals to a larger audience, “We’re expecting up!”

– 3 –

Size Up

Looking up to the inherent dignity of every person and then matching it with right expectations are vital to motivating and empowering people. However, doing this is no more important than measuring the results. If we don’t “size up” or compare our results to our own expectations, we’ll never know if the cultural and programmatic changes we’ve made are actually making the difference we hope to see. We must measure what matters. Beyond outputs like number of meals, pounds of food, nights of shelter, etc., we must establish outcome domains like employment, social capital, and spiritual growth as well as the indicators that help meter progress in those areas. These may include jobs landed, social capital score changes, or progress on the Engel Scale (a spiritual-growth measurement tool).

For example, at Watered Gardens Ministries, we have three primary outcome domains for most measurements: Connections, Career, and Character. Under our outcome domain “Connections,” we measure how well we do at reconnecting people to family or helping them form new relationships in the Church. So we now also measure recidivism, with a hope to see people will be returning less to our shelter!

Sizing up requires brutal honesty and painful humility. My experience has been that when sizing up the progress in our programs, we often have to swallow our pride and make changes in the ways we’re doing things. Outcome development and training is worth the time and effort. Remember, Jesus came to radically change lives. That change is measurable.

– 3 –

Size Up

Looking up to the inherent dignity of every person and then matching it with right expectations are vital to motivating and empowering people. However, doing this is no more important than measuring the results. If we don’t “size up” or compare our results to our own expectations, we’ll never know if the cultural and programmatic changes we’ve made are actually making the difference we hope to see. We must measure what matters. Beyond outputs like number of meals, pounds of food, nights of shelter, etc., we must establish outcome domains like employment, social capital, and spiritual growth as well as the indicators that help meter progress in those areas. These may include jobs landed, social capital score changes, or progress on the Engel Scale (a spiritual-growth measurement tool).

For example, at Watered Gardens Ministries, we have three primary outcome domains for most measurements: Connections, Career, and Character. Under our outcome domain “Connections,” we measure how well we do at reconnecting people to family or helping them form new relationships in the Church. So we now also measure recidivism, with a hope to see people will be returning less to our shelter!

Sizing up requires brutal honesty and painful humility. My experience has been that when sizing up the progress in our programs, we often have to swallow our pride and make changes in the ways we’re doing things. Outcome development and training is worth the time and effort. Remember, Jesus came to radically change lives. That change is measurable.

– 3 –

Size Up

Looking up to the inherent dignity of every person and then matching it with right expectations are vital to motivating and empowering people. However, doing this is no more important than measuring the results. If we don’t “size up” or compare our results to our own expectations, we’ll never know if the cultural and programmatic changes we’ve made are actually making the difference we hope to see. We must measure what matters. Beyond outputs like number of meals, pounds of food, nights of shelter, etc., we must establish outcome domains like employment, social capital, and spiritual growth as well as the indicators that help meter progress in those areas. These may include jobs landed, social capital score changes, or progress on the Engel Scale (a spiritual-growth measurement tool).

Looking up to the inherent dignity of every person and then matching it with right expectations are vital to motivating and empowering people. However, doing this is no more important than measuring the results. If we don’t “size up” or compare our results to our own expectations, we’ll never know if the cultural and programmatic changes we’ve made are actually making the difference we hope to see. We must measure what matters. Beyond outputs like number of meals, pounds of food, nights of shelter, etc., we must establish outcome domains like employment, social capital, and spiritual growth as well as the indicators that help meter progress in those areas. These may include jobs landed, social capital score changes, or progress on the Engel Scale (a spiritual-growth measurement tool).

For example, at Watered Gardens Ministries, we have three primary outcome domains for most measurements: Connections, Career, and Character. Under our outcome domain “Connections,” we measure how well we do at reconnecting people to family or helping them form new relationships in the Church. So we now also measure recidivism, with a hope to see people will be returning less to our shelter!

For example, at Watered Gardens Ministries, we have three primary outcome domains for most measurements: Connections, Career, and Character. Under our outcome domain “Connections,” we measure how well we do at reconnecting people to family or helping them form new relationships in the Church. So we now also measure recidivism, with a hope to see people will be returning less to our shelter!

Sizing up requires brutal honesty and painful humility. My experience has been that when sizing up the progress in our programs, we often have to swallow our pride and make changes in the ways we’re doing things. Outcome development and training is worth the time and effort. Remember, Jesus came to radically change lives. That change is measurable.

♦ ♦ ♦

Looking up, expecting up, and sizing up is a simple formula to answer the call of our cities and our nation. More importantly, it is the way we empower people in poverty and honor God who has entrusted us with a mission so close to His heart. May God’s peace, passion, and wisdom continue to reign in your life and direct your calling!

Reprinted with permission from Citygate Network. All rights reserved.

Avery West

Avery West

For example, at

For example, at